The labour market

The labour market

Demand for labour

The demand for labour is the willingness and ability for a firm to hire workers at a given wage rate. It is determined by the Marginal Revenue Product (MRP), which is the additional revenue gained from each extra worker hired.

Derived demand for labour

The demand for labour is usually described as a derived demand, since the demand for workers to be hired is derived from the demand of goods and services in that sector.

Factors that affect the demand for labour

Wage rates: As wage rates increase, the demand for labour contracts, since firms are getting the same amount of labour, but at a higher cost which does not allow them to maximise profit.

Demand for the product produced: If the demand for the product produced rises, it derives an increase in demand for labour in that sector, since the firms look to respond to the rise in demand by extending supply.

Regulation: When lots of regulation exists in a labour market, it is likely for the demand for labour to be low. This is because the hiring of workers may be very time consuming or can have excessive administration costs.

Advancements in technology: Advancements in technology may mean that the demand for labour is reduced. This is because technology is able to execute the same job as a human to the same standard or better in some cases, at a potentially cheaper price.

Price Elasticity of Demand (PED) for labour

The Price Elasticity of Demand (PED) for labour is the responsiveness of quantity demanded for labour to a change in the wage rate in a labour market.

Factors affecting the PED for labour

PED for the product: The PED of a product is directly correlated to the PED of labour in that sector. This is because if a good is elastic and the price rises due to an increase in wages, there will be a more than proportionate contraction in demand for that product, so this means that firms will have to shed lots of labour to retain supernormal profits.

The proportion of wages in the cost of production: If the proportion of wages in the cost of production is small, it is likely that PED will be inelastic, since a change in the wage rate will not hugely change the cost of production.

The number of substitutes: If there are a large number of substitutes, such as machinery, then PED for labour will be elastic, since the problem of an increase in the wage rate can be mitigated by using machinery instead.

Time period: In the long run, PED is more elastic since there has been more time for firms to find substitutes and cheaper options to the current labour.

Supply of labour

The supply of labour is the willingness and ability of a certain quantity of households to give their labour to firms at a certain wage rate.

Factors that affect the supply of labour

Wage rates: The labour supply curve is shaped as a bending backwards curve, since an increase in the wage rate will increase the supply of labour up to a certain point. After this point, the supply of labour will contract due workers not needing to work as much anymore for the reward of income that they need to live on.

Size of population: If the size of the population is larger, the supply of labour is likely to increase, since there are more people available to work. The size of the population can increase from migration, which will increase the supply of labour, especially if the vast majority are economic migrants.

Fringe benefits: If there are more fringe benefits in the workforce, it may provide an incentive for households to join the workforce even if the wage rate does not change.

Level of education: More educated workers mean that there will be a higher supply of labour. This is especially true in sectors that require qualifications to work in them.

Price Elasticity of Supply (PES) for labour

Price Elasticity of Supply (PES) for labour is the responsiveness of the quantity of workers willing and able to supply their labour to a change in the wage rate in a labour market.

Factors that affect the PES for labour

Time period: In the long run, PES for labour will be more elastic since workers will have more time to train and thus join the workforce.

Level of education: If a job requires high amounts of qualifications or experience, it is likely that PES for labour will be inelastic. This is because it is not easy to replace workers in these types of jobs.

Significance of vocational aspects: If there are vocational aspects in a job, then PES is likely to be more inelastic because workers are not necessarily working only for the wage rate, so they will be less responsive to changes in the wage rate.

Market failure in labour markets

Occupational immobility

Occupational immobility occurs when a worker cannot move jobs due to a lack of skills needed in a new industry.

Solutions

Government training schemes: Providing funding and programs to workers can help them learn skills, which may make them more occupationally mobile in the future.

Apprenticeships: Apprenticeships offer hands-on experience and training, allowing workers to gain practical skills in a specific trade.

Skill development grants: Giving financial support to workers in order to access courses and certifications may improve their employability in certain sectors.

Geographical immobility

Geographical immobility occurs when workers cannot move jobs because of their geographical location, preventing them from commuting to a new industry.

Solutions

Affordable housing initiatives: Building or subsidising houses near key employment hubs can reduce employment barriers, due to geographical reasons.

Remote work options: Introducing remote work options, removes geographical location as a barrier to employment. This reduces geographical immobility as a whole.

Development of infrastructure: Improving transport links can reduce commuting times and make it more affordable thus reducing geographical immobility.

Wage rate determination in different markets

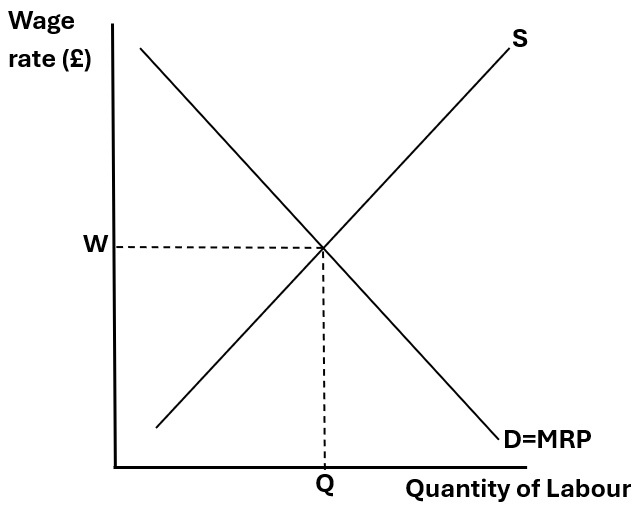

Perfect competition

In a perfectly competitive market, wage rates are decided by the equilibrium of demand and supply, and all workers are paid the same (at wage rate, W).

Bilateral labour markets

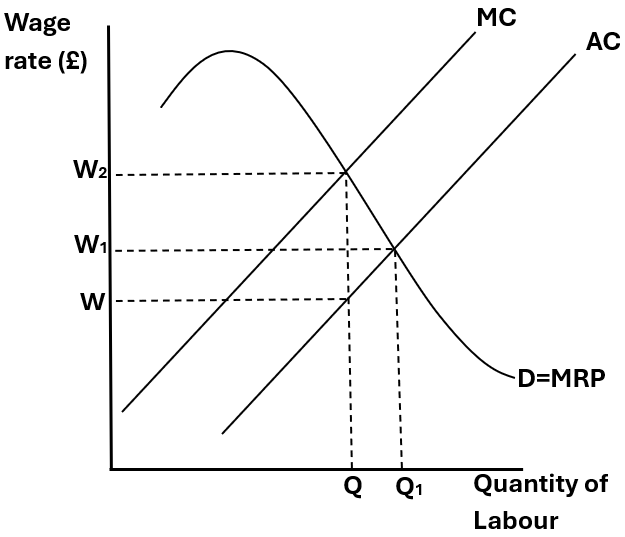

A bilateral labour market is one that includes a monopoly supplier of labour and a monopsony buyer of labour. A monopoly supplier of labour could be a trade union and a monopsony buyer could be an organisation such as the NHS that purchase the labour of doctors or nurses.

In a bilateral labour market, the wage rate is set, dependent on whether the monopoly supplier or the monopsony buyer is stronger. If the monopsony buyer is more powerful, the wage rate would be set closer to W, whereas if the monopoly supplier is more powerful, the wage rate would be higher, close to W2.

The middle ground of W1 represents a compromise between the monopsony buyer and the monopoly supplier, where benefits have been provided to both parties. These benefits are an increase in the quantity of labour from Q to Q1 for the monopsony buyer and an increase in the wage rate from W to W1 for the monopoly supplier.

If the wage rate is at W, then the market wage rate is completely set by the monopsony buyer, and if it is set as W2, then the wage rate is completely set by the monopoly supplier. This is no longer a bilateral labour market.

Problems in the labour market

Strikes: Strikes disrupt worker productivity since it removes the number of days worked by the labour force. This can become a problem in the labour market and disrupt the market equilibrium for wages.

Size of working population: A shrinking working population, caused by an ageing population or outward immigration, can reduce the supply of labour in a country, often changing the market wage rate.

Skills shortages: Insufficiently skilled workers in certain industries can create inefficiencies and slow growth in certain sectors.

Wage inequality: Significant wage disparities in the labour market can reduce social cohesion and create social tensions which harm economic stability.

Minimum and maximum wages

Minimum wages

This is when a price floor is set in the labour market, and the wage rate is not able to go below this level.

Advantages

Poverty reduction: A minimum wage ensures that workers will earn enough to meet their basic living standards, thus reducing poverty.

Ensures a "fair wage": This protects workers from being exploited by their employers by establishing a baseline for compensation.

Efficiency wage theory: Higher wages can improve worker productivity, which benefits the firm by increasing output, and also increases the prospect for promotion for the worker.

Disadvantages

Shirking model: Higher wages may not always lead to productive behaviour, since workers may choose to shirk if there is a minimum wage in place. This is because workers know that if they are fired from a minimum-wage job, they can find another job with the same pay.

Increased labour costs: A minimum wage will lead to firms paying more for labour, thus increasing labour costs.

Wage spiralling: A rising minimum wage can lead to demand for higher wages across the pay scale, which can lead to negative effects such as inflation.

Maximum wages

This is when a price ceiling is set in the labour market, ensuring that the wage rate does not go above this level.

Advantages

Reduces income inequality: Providing a maximum amount a worker can earn will close the gap between the lowest and the highest earners, thus reducing income inequality.

Incentivises higher wages for lower earners: If the highest earners are capped at a certain point, it may give firms spare resources which they can use to pay the lowest earners more. This may increase their productivity and help contribute to a more even distribution of income.

Disadvantages

"Brain drain": Highly skilled individuals on high salaries may leave the UK to work in other countries without wage restrictions, leading to a loss of high-skilled workers.

Decreased productivity: A cap on income may reduce the incentive for individuals to work harder, thus leading to a reduction in productivity levels.