Competition and markets

Efficiency

Allocative efficiency

Allocative efficiency occurs when resources are allocated in a way that maximises social welfare; it is achieved when the distribution of goods and services aligns with consumer preferences. At the allocatively efficient level of output, the marginal cost (MC) equals the marginal benefit (MB), thus ensuring that resources are not underutilized or overused.

Productive efficiency

Productive efficiency is achieved when a firm produces goods and services at the lowest possible cost; producing at the point where the average total cost (ATC) is minimized. Productive efficiency is essential for ensuring that resources are used efficiently and promotes cost-effectiveness and reducing waste.

Dynamic efficiency

Dynamic efficiency refers to a firm’s ability to innovate, adapt and improve over time. A dynamically efficient firm invests in research and development, embraces advancements in technology and constantly seeks ways to enhance productivity. This is crucial in dynamic markets where change is frequent, as firms must stay competitive and responsive to consumer demands.

X-inefficiency

X-inefficiency occurs when a firm is not operating at the minimum possible cost due to a lack of competition or other market imperfections. In competitive markets, firms are motivated to be efficient to survive. however, X-inefficiency may arise in situations where competition is weak, as firms have a reduced incentive to minimise costs.

Efficiency/inefficiency in different market structures

Perfect competition: Firms are price takers; allocative and productive efficiency are likely to be achieved due to intense competition.

Monopolies: The firm's behaviour may lead to reduced allocative efficiency because they have the market power to set prices higher than the competitive level.

Oligopolies: The firms in an oligopoly may experience both efficiency and inefficiency, depending on the nature of competition and strategic behaviour.

Monopolistic competition: In monopolistic competition, firms may experience some inefficiency due to product differentiation and excess capacity.

Perfect Competition

Characteristics of perfect competition

Large number of buyers and sellers: None of the numerous buyers and sellers in the market have the power to influence the market price.

Homogenous products: Firms produce identical or perfectly substitutable products (this ensures that consumers see no differences between products of different firms)

Perfect information: Both buyers and sellers have complete knowledge about the market, prices, and products (thus ensuring that profits are driven to normal levels in the long run)

Free entry and exit: Firms can enter or leave the market without barriers, thus promoting competition.

Price takers: Individual firms have no control over the market price; they must adjust their quantity supplied based on the prevailing market price.

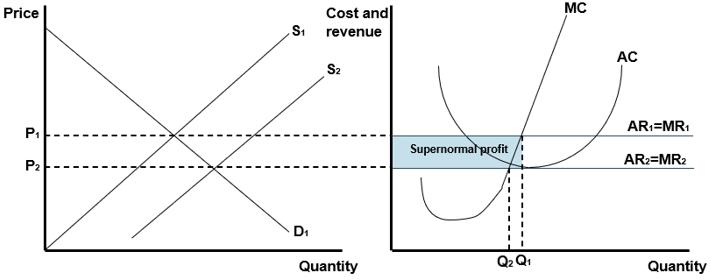

Profit maximising equilibrium in the short run and long run

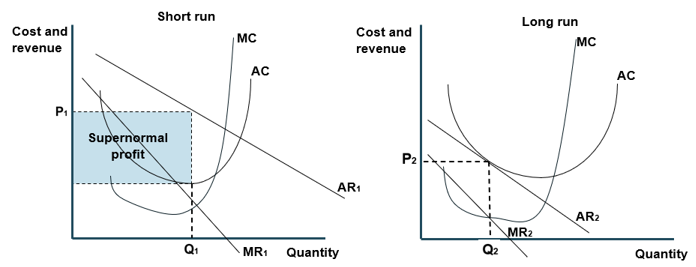

Short run:

In the short term, a firm maximises profits by producing the quantity where MC = MR (where MR is marginal revenue). If the market price is above the average variable cost, the firm continues production. Conversely, if it is below average variable cost, the firm may shut down in the short run to minimize losses. The economic profit or loss is calculated by considering total revenue, total cost, and opportunity costs.

Long run:

Firms can enter or exit the market based on profits or losses. In the long run equilibrium, firms earn normal profits zero economic profit). The market price equals the minimum average total cost, ensuring that resources are efficiently allocated.

Monopolistic competition

Characteristics of monopolistically competitive markets

Large number of sellers: Each of these many firms produces a slightly differentiated product.

Product differentiation: Products are not perfect substitutes; firms compete through branding, quality, and other features.

Free entry and exit: As with perfect competition, new firms can enter the market easily and existing firms can lease it without significant barriers.

Limited price control: Firms have some control over their products due to product differentiation, but they are still price takers to some extent.

Independent decision-making: Firms make decisions independently, without significant influence on the market price.

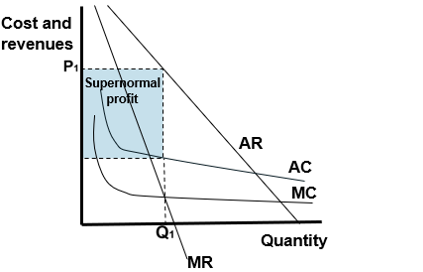

Profit maximising equilibrium

In the short run, profit can be positive, negative or zero. In the long run, firms can enter or exit the market freely. If there are profits in the industry, new firms will enter, increasing competition, reducing prices, and reducing profits. Conversely, losses in the industry may lead firms to exit the market. In the long run, firms tend to earn normal profits, and economic profit approaches zero.

Oligopolies

Characteristics of oligopolistic markets

High barriers to entry and exit: Oligopolistic markets often have significant barriers that make it difficult for new firms to enter or existing firms to exit. These barriers include high startup costs, economies of scale, legal restrictions, and access to resources.

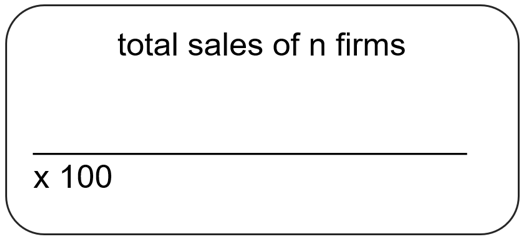

High concentration ratio: Oligopolies are characterized by a small number of large firms dominating the market. The concentration ratio measures the proportion of market share held by a specified number of the largest firms.

Interdependence of firms: Decisions regarding pricing, output, or product innovation by one firm can lead to strategic responses from competitors, as the actions of one firm significantly impacts the others.

Product differentiation: Oligopolistic firms engage in product differentiation to make their products appear distinct from those of competitors – this can be done through branding, unique features, or advertising.

Kinked demand theory

The kinked demand curve theory suggests that in an oligopoly, firms face a demand curve with an elastic range above the existing price and an inelastic range below it. If a firm increases its price, rivals might not also raise prices, with a fear of losing market share. Conversely, if a firm decreases its price, rivals are likely to do the same, thus resulting in a stable price level. This theory helps explain why prices in certain oligopolistic markets may remain relatively stable over time

Calculation n-firm concentration ratios and their significance

Concentration ratios measure the extent to which a small number of firms dominate the market. The n-firm concentration ratio calculates the combines market share of the top “n” firms. High concentration ratios indicate market dominance, whereas low ratios suggest a more competitive market. It is worked out by adding the percentages of market share for the firms or using the formula:

Reasons for collusive and non-collusive behaviour

Profit maximisation: Firms in an oligopoly may collude to reduce uncertainty and maximise joint profits. Collusion can take the form of price-fixing, output quotas or market-sharing agreements.

Difficulty in sustaining collusion: Oligopolistic firms may engage in non-collusive behaviour due to the difficulty of reaching (and sustaining) collusion. Factors such as the temptation to cheat, the presence of antitrust laws and a general lack of trust can discourage collusion.

Overt and tacit collusion

Overt collusion

Overt collusion occurs when firms openly coordinate their actions to manipulate the market. It involved explicit agreements among firms to fix prices, limit production or allocate markets. Overt collusion is often illegal; it restricts competition and therefore harms consumer welfare. Thus, to prevent such collusion, anti-trust laws are in place in many countries.

Tacit collusion

Tacit collusion happens when firms coordinate their actions without explicit communication or formal agreements. Firms may observe each other’s behaviour and act in ways that align with mutual interests (even though there is no direct communication). Tacit collusion can be difficult to prove, but can still lead to anti-competitive outcomes.

Cartels

A cartel is a formal agreement among a group of firms in an industry to coordinate their activities, usually to fix prices, limit production or allocate market resources.

Cartels are usually secretive and involve a high degree of cooperation among participating firms. The aim is to reduce uncertainty and increase the profitability of all cartel members.

However, challenges may arise in the form of maintaining discipline among members, as individual firms may be tempted to cheat by lowering prices or increasing production to gain a competitive advantage over others.

Price leadership

Price leadership is a situation where one dominant firm in an industry (which is the largest, most efficient or has a unique competitive advantage) sets the price and the other firms in the market follow its lead.

There are two main types of price leadership: Explicit (formal) price leadership occurs when the leading firm openly communicates and sets the price, and the other firms in the industry follow suit.

On the other hand, implicit (informal) price leadership happens when other firms observe the pricing behaviour of the leading firm and voluntarily adjusts their prices.

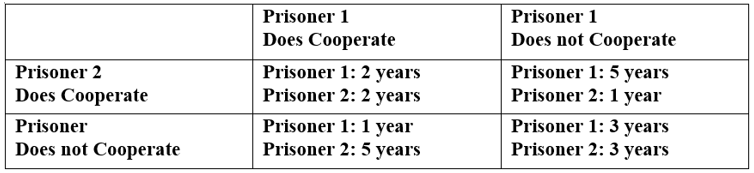

Simple game theory

Game theory is a branch of economics that studies strategic interactions between rational decision-makers. It is often used to analyse situations where the outcome of one participant’s decision depends on the decisions of others.

In a two-firm scenario, the prisoner’s dilemma is a situation where both firms may benefit from cooperating, but due to the fear of the other firm not cooperating, they end up choosing strategies that are not best for each other.

Types of price competition

Price wars: Businesses may lower prices rapidly to gain market share, when facing intense competition.

Predatory pricing: A firm may set prices below average variable costs with the intent to drive competitors out of the market. However, this is anti-competitive and may lead to market dominance concerns.

Limit pricing: Setting prices low to deter new entrants into the market or to limit the market share growth of existing competitors.

Types of non-price competition

Product differentiation: A product can be made distinct through features, quality, or branding.

Advertising and marketing: Creating awareness and building brand loyalty through promotional activities.

Innovation: Introducing new products or improving existing ones to attract customers based on product uniqueness.

Customer service: Enhancing the overall customer experience by providing excellent services.

Monopolies

A monopoly is characterised by a single seller dominating the market, controlling the supply of a unique product with no close substitutes. The lack of competition may be due to high barriers to entry, such as high start-up costs or exclusive access to resources.

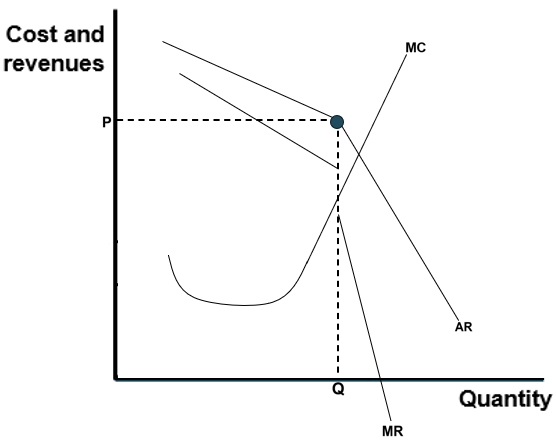

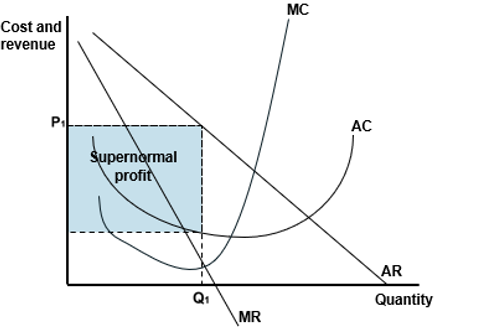

In a monopoly, profit maximisation happens when marginal revenue (MR) equals marginal cost (MC). The monopolist produces the quantity where MR=MC and sets the price on the demand curve corresponding to that quantity.

Profit maximising equilibrium

Third degree price discrimination

Necessary conditions include market segmentation, differences in price elasticity and prevention of resale. Third degree price discrimination involves setting different prices for distinct consumer groups. Producers may benefit from increased revenue, while consumers may experience varied prices based on their willingness to pay.

Advantages and disadvantages of a monopoly

A monopoly can lead to higher prices and reduced output, thus negatively impacting consumers. However, firms may benefit from supernormal profits, from which innovation may arise. While employees may also benefit from increased job security, suppliers can face high pressures to lower prices.

Natural monopolies

Natural monopolies occur when a single firm can most efficiently provide goods and services due to economies of scale. This can often lead to the most cost-effective outcome for society, but regulation is crucial to prevent abuse of monopoly power.

Monopsonies

Characteristics of a monopsony

Dominant buyer: A single buyer in the market for a particular type of labour or product.

Market power: The monopsony has significant market power, thus allowing it to influence the price by controlling the quantity of goods and services demanded.

Sets barriers to entry: Barriers to entering the market.

Limited information: Lack of information available to sellers about alternative buyers or market conditions may strengthen the monopsonist’s position.

Impacts on various stakeholders

Firms: Firms may experience lower prices for inputs, potentially leading to reduced profit margins. However, the monopsonistic buyer can negotiate favourable terms with suppliers (enhancing cost efficiency).

Consumers: If the monopsony can extend market power to achieve supernormal profits, consumers may face higher prices for goods and services. However, in certain cases, lower costs for the buyer with the monopsony may translate into lower prices for the consumer.

Employees: Workers may face reduced wages due to reduced competition among employers. On the other hand, the monopsony may provide a more secure job market which may lead to stable employment opportunities.

Suppliers: Suppliers may have to accept lower prices for their goods and services, but regular and stable demand from the firm with the monopsony can provide a predictable market for suppliers.

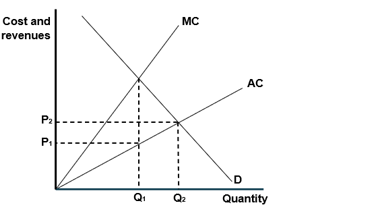

Contestability

Contestable markets are characterised by low barriers to entry and exit: new firms can enter and existing firms can exit the market easily. This means that it is a market with a high threat of new entrants, keeping firms productively efficient.

Characteristics of contestable markets

Perfect knowledge: if one firm is able to make unordinary profits, it is assumed that other firms will enter the market

Product Loyalty: Loyalty to firms is low, meaning that consumers are willing to switch if new firms join or replace established firms in the market.

Short-Run Profit Maximising: Firms do not collude with each other.

Freedom of entry and exit: Any firms will be able to enter and leave the market at any time, with an absence of sunk costs. Average costs for new firms will also be similar to established firms.

Implications

In contestable markets, firms are seen to be productively efficient, and allocative efficient.

Firms are only able to make normal profits, because if prices were higher, new firms would join the market and undercut them. This means AR=AC.

Firms enter the market if abnormal profits are made, taking away profits from other firms, by undercutting new firms. However, this can be mitigated by limit pricing.

Sunk costs

Sunk costs are costs to a business that is not recoverable when a producer leaves the market. Sunk costs are usually a part of the firms original fixed costs. For example, if a manufacturer had warehouses and decided to leave the market, if the producer had no use for the land anymore and decides to sell it, they may accumulate sunk costs where they sell the factors of production for less than they paid for it. All firms face sunk costs when they leave a market, because capital can be scrapped, and even if it is resold, it may be for a cheaper price due to its second-hand nature.

Degree of contestability

The degree of contestability is defined as the extent that the benefit from entering a market compares to the costs of entering a market. A market where barriers to entry and sunk costs do not exist, is an example of a perfect contestable market. However, in reality, no markets are likely to be perfectly contestable because sunk costs and barriers to entry are almost always imminent.

Barriers to entry and exit

Barriers to entry and exit are intangible forces that stop new firms from entering or leaving the market. There are two types of barriers to entry and exit: natural barriers and anti-competitive barriers. Natural barriers are economic forces that do not intentionally stop alternate firms from entering the market, whereas anti-competitive barriers are forces that are implemented to limit or maximise the number of firms in a market, usually by intent.

Natural barriers to entry

Economies of scale: Established firms may have lower average costs due to the increase in the scale of their operations. New entrants may struggle to achieve similar levels of efficiency due to a smaller scale of production.

Network effects: In certain industries, the demand for a product may increase due to a rise in users. Network effects are known as "demand-side" barriers to entry and an example could be purchasing apple products, to use the same data across devices. New firms with decreased demand for their products may find it hard to compete when firms have existing high levels of demand.

Capital requirements: Certain industries may have huge capital requirements just to survive in the market, let alone make a profit. This may make it incredibly difficult to enter the marketplace, particularly in industries such as the airline industry, where they have huge capital and labour costs.

Natural barriers to exit

High fixed costs: Industries may involve high fixed costs, which can lead to challenges when trying to leave a market due to substantial investments already being made. Leaving the market may create huge losses, making it financially unfeasible for firms.

Long-term contracts: Firms may be locked into long-term agreements with suppliers making it difficult to leave the market without legal or financial consequences. In some cases, the price to buy oneself out the contract may be too large to exit the market at a financial gain

Specialised factors of production: Firms may have specialised equipment, used in their operations which could be difficult to sell which creates large sunk costs. If the magnitude of these sunk costs are high, firms may not be able to afford to leave the market.

Anti-competitive barriers to entry

Predatory pricing: Incumbent firms may temporarily decrease prices to drive out new competitors in the market that are unable to deal with the price cuts. This may make it difficult for new firms to enter a market.

Exclusive contracts: Firms may intentionally make contracts with important suppliers to supply specialised raw materials exclusive, creating a huge challenge for other firms to find the relevant or needed raw materials to survive in that specific market.

Brand recognition: Firms may differentiate their products to exclude other firms in the marketplace, and make their goods and/or services more attractive to consumers. This may intentionally prevent producers from entering the market as they would not be able to compete with the effective marketing in place.

Anti-competitive barriers to exit

Cartels: If firms are colluding in oligopolistic markets, it may serve as a barrier to exit if one firm were to decide to leave. This is because they may face pressure to stay in the market to uphold cartel agreements. Exiting the market may disrupt the stability of the cartel and lead to retaliatory measures.

Brand damage: Established firms may engage in campaigns that aim to damage the reputation of leaving firms. The spread of of misinformation or negative publicity can create pressures on producers to stay in the market and protect their own position.